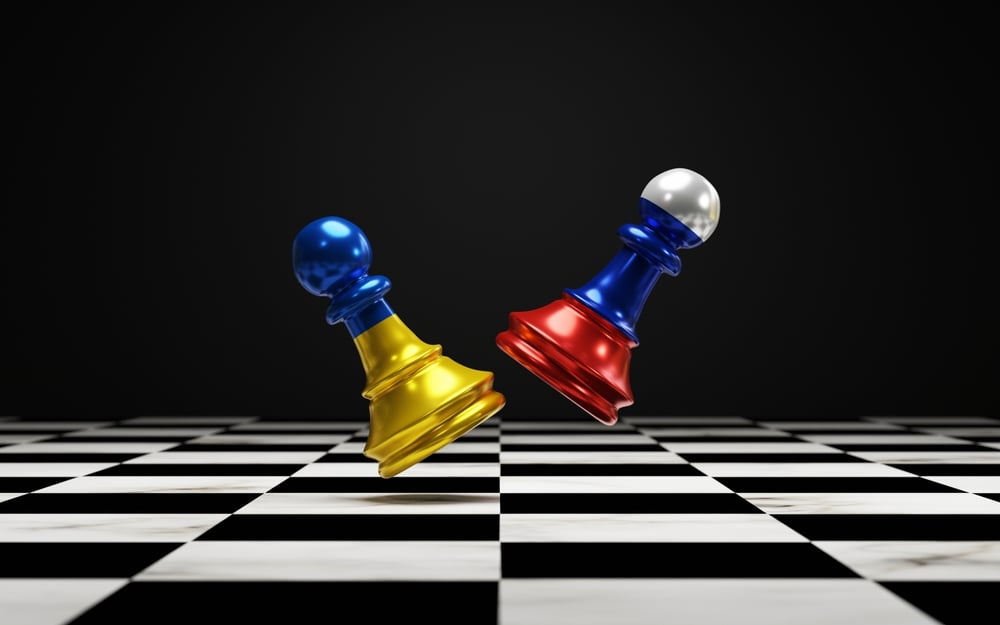

A new front has opened in the war between Russia and Ukraine, but this time battleground is not being fought in the towns and streets of the embattled European nation but through the internet’s shadowy mirror: the darknet.

Earlier this year German authorities raided the premises of the largest darknet market on the planet, seizing $25 million in Bitcoin for their efforts. Since 2017 Russian-language site Hydra dominated the illegal drug business in Eastern Europe.

The fall of Hydra was more than just the end of a drugs marketplace however, the site offered forged documents, hacking, and money laundering services. Its end marked another body blow for the west against Russian-speaking cybercriminals and underscores a period of shifting allegiances in Ukraine.

From East to West

At one time Ukrainian and Russian criminals were as thick as cyberthieves, but those relationships are increasingly strained.

Senior Washington analyst András Tóth-Czifra explained how that union has been cleaved apart since 2019.

As Tóth-Czifra reported to Aljazeera this week, Russian criminals felt “a growing unease that Ukraine was co-operating with Western cyber-police, which itself was a consequence of Western countries providing aid to strengthen Ukraine’s cyber-defences.”

Tóth-Czifra, who works for DC-based firm Flashpoint Intelligence says that Ukrainian criminals “suddenly faced higher risks. And yes, afterwards, there were larger arrests.”

Post-Hydra traders fled to RuTor, a Russian-speaking cybercrime forum believed to operate within the Ukrainian sphere of influence.

The RuTor darknet rumor

The migration of Hydra vendors to RuTor only fueled the notion that the site was being run by the Ukrainian security services (SBU). A pro-Kremlin group of hacktivists called Killnet then mobolized to take RuTor down via a DDoS (distributed denial-of-service) attack.

Tóth-Czifra says, “when Killnet drew on its followers to commit DDoS attacks against RuTor, they depicted RuTor as an SBU forum. One thing Killnet has certainly been doing is trying to get support from the state; they have been quite open about that.”

“It wasn’t an explicit attack against narcotics marketplaces, it was an attack on marketplaces that allegedly have connections to Ukraine,” expanded Vladislav Cuiujuclu, another team member at Flashpoint.

Some of those battles do appear to take place at a civilian level.

Cuiujuclu said, “A definite change we have seen in the past nine months is the appearance of collectives that primarily focused on DDoS, but what’s really important is they openly recruit people on Telegram…. According to the admins of these groups, they recruited hundreds and thousands of people who allegedly are volunteers.”

Putting profits first

While hacktivists wage their war the picture of who is directing what remains confused. What exactly their links are to security services on both sides of the divide is difficult to say, and declarations of support can be tricky.

When ransomware group Conti swore allegiance to Russia a Ukrainian insider blew the group open by leaking their chat logs. Lifting the lid did seem to suggest that the group potentially had links with Russian intelligence.

Whoever runs the sites, Russians or Ukrainians, criminals are finding ways to survive and even thrive. Russian newspaper Novaya Gazeta found that even as bombs fell on Kherson and Mariupol the drugs continued to flow.

In the end, whoever wins the battle to control Ukraine, its bomb-pitted streets will still belong to the dealers.

and then

and then